John Lithgow on Exposing Vulnerability, Sadness and His Legs in Hillary and Clinton

Two-time Tony Award winner John Lithgow may not really look like the 42nd President of the United States, but both accomplished men have one thing in common: they know about popular. That commonality is serving Lithgow well as he embodies Bill alongside Tony winner Laurie Metcalf's Hillary without the help of the typical actors’ tools of the trade in the new play Hillary and Clinton. The marriage of the Clintons has been turned into provocative drama by playwright Lucas Hnath (A Doll’s House, Part 2) on basically a bare stage with no wigs, make-up or accents and costumes that are more comfy than classy (more on that later). Still, the stars pull off the yin and yang of the political dynamos beautifully, with Lithgow’s likable ease a great match for his real-life counterpart. Broadway.com caught up with Lithgow in his dressing room to talk about the politics of putting on a play like Hillary and Clinton.

I think many would agree that Bill Clinton seems like a guy who'd be fun to hang out with. What’s it been like for you to hang out with him as a character for the past few months?

I’ve certainly loved playing the part. It’s not exactly Bill, which is what’s been liberating about it. It’s not a dogged imitation of him. I spent not a second in front of the mirror imitating him. Lucas has written this ingenious play, which kind of liberates both the actors and the audience from any feeling of obligation toward verisimilitude. It’s not like playing Churchill [on The Crown] or Roger Ailes [in the upcoming film Fair and Balanced], which are the two people I’ve impersonated in the last couple of years. This is almost entirely me, riffing in a speculative way on recent history. The operative word is recent because Bill and Hillary are still very much part of our worlds.

And the Broadway world. They see shows all the time.

They see every show except ours. I don’t believe they’ll be coming to ours, which is a pity. I certainly don’t blame them. We invited them to come to see a command performance with nobody else in the theater, but I think it’s hard for them. It would be hard for me to come and see a warts-and-all take on me. I wouldn’t want to see that.

Performing Hillary and Clinton for just Hillary and Clinton would be something.

I thought it was a very kindly and generous offer on [producer] Scott Rudin’s part. After all, thousands of people are seeing this. They’re thinking about them. They’re empathizing with them, but they’re also laughing at them. That can’t be an entirely comfortable thing to know is even happening. On the other hand, this is the way they lived their lives the last 40 years. Scott had a lunch with them and the one quote that was passed onto us is that Bill, having read the play, said, “Well, it’s nothing that hasn’t been printed a thousand times in the press.” I mean, my own feeling is that we’re honoring them with this—at least, you have to approach it that way. We are certainly not taking them down. It’s a seriously intended play examining a couple under incredible pressures, pressures that none of the rest of us can possibly imagine.

Didn't you campaign for Hillary during her last run?

I know them—I mean, I’ve met them on both formal and informal occasions. Put together, probably five or six times. And I admire them. I campaigned for Hillary. I voted for Hillary. I grieved when Hillary did not win the presidency, and I think her loss in that election is one of the great, grave disappointments of our times. The consequences are enormous. She would have been such a fine president. The very interesting thing about this play, more than any other play I’ve been in, is the baggage that an audience brings in—their own emotions and their politics. That’s pretty exciting stuff to deal with in a theater. It’s explosive, and that’s what we look for, we actors.

Without accents, costumes or wigs, you and Laurie Metcalf are really capturing the essence of Bill and Hillary in exciting ways. What was it like in the rehearsal room finding that rhythm with her?

Everything was effortless with Laurie. I mean, we worked hard and Joe Mantello is a very challenging director. I’m so grateful for that. We really worked very closely with Lucas; it underwent a lot of changes. But the actual acting process with Hillary—er, Laurie, is completely exhilarating.

You can call her Hillary.

[Laughs.] It’s an easy mistake to make. I mean, I’m a mediocre tennis player, but when I play with a really good tennis player, I really play well. And she just…man! She just gives back. She throws everything back. She’s got quicksilver responses on stage and is completely real and engaged. She’s a huge reason why I took the job. We had worked before on 3rd Rock from the Sun. She did a hilarious three-episode arc going from the ecstasy to the agony of a misbegotten love affair. She was absolutely hilarious as my foolish character Dick Solomon realized he made a catastrophic mistake. [Laughs.] She just really went for it!

As she does.

She never leaves a thing in the dressing room. She’s just a powerhouse actress. I consider her like our Anna Magnani. She’s just pure passion, and I love it.

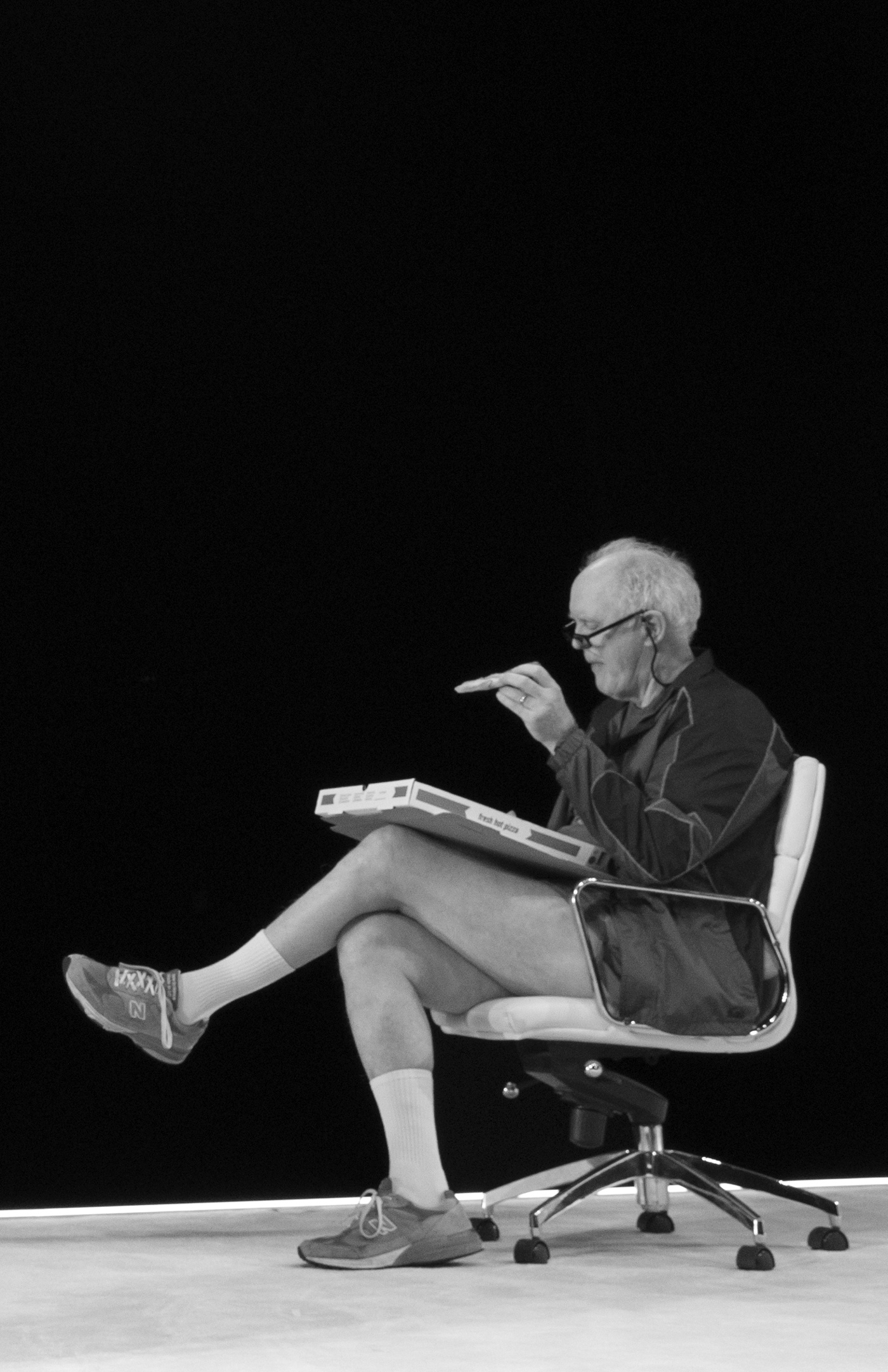

OK, now let’s talk about your shorts in the show. Broadway’s talking about your legs.

[Laughs.] I was self-conscious about it. No doubt about it. I thought it was a great visual but I couldn’t imagine sustaining it for the entire second act of the play. I rehearsed with them out of respect to Joe and it was great. It was so disarming. It’s a very familiar Bill look, and it also makes him very comfortable and at ease and impervious. Terrible things are hurled at him and he just sits there with a little smile on his face. He takes it all. In the same sense, I bear my fish-belly white legs for a full Broadway house every performance and I don’t give a shit. You know? [Laughs.]

(Photo by Julieta Cervantes)

I love that.

It was all Joe and Rita Ryack, our terrific costume designer. They were strategic in gradually persuading me, but I was persuaded. It reminds me of when I played Roberta Muldoon in the movies. [Lithgow played the trans character in 1982’s The World According to Garp early in his career.] For the first couple of scenes, Roberta is kind of a sight gag—a great big, familiar actor dressed in drag. But by the third scene, she’s sobbing because she can’t have children and you have to take her completely serious. By the same token, the first time in Hillary and Clinton you see me carrying my box of pizza and my crosswords in my running shorts, it’s a sight gag. But ultimately Bill becomes sad and vulnerable. He’s exposed, figuratively and literally; I think it’s very effective.

So, what do you think we can all take away from Hillary and Clinton?

A friend of mine, David Maraniss, won a Pulitzer Prize covering Bill Clinton and wrote a Clinton biography, First in His Class, and found the show enormously cathartic because it was a speculative and fictional version of the one thing he couldn’t get: past the door into the private life of these two people. And nobody got to know them better than David Maraniss! But ultimately, they were elusive. Theirs is a story of great triumph and great disappointment, and all of us of a certain political persuasion have lived through that with them. Catharsis is the word. I think the play exercises all those emotions. There is a tremendous melancholy and sense of disappointment that is an undertone of the entire play, and it finally really hits you at the end. I think it’s addressing a certain sadness in our times.

As a Hillary supporter yourself, has this experience been cathartic for you personally?

Well, I do feel for them. I don’t know… This whole thing has been an experiment. We sprung this on the public, and we’re asking them to think about things that we have our own strong feelings about. But I do wonder and worry about what they think, there’s no doubt about it. Because my heart goes out to those two after all they’ve been through. That’s why I keep saying we really do want to honor them. In the end, that’s always been our intention.